Herbert McKell

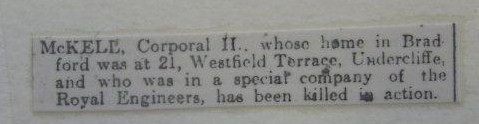

Corporal 106636 3rd Special Company Royal Engineers.

Buried in Villers Station Cemetery, near Arras, France

Commemorated on his parents’ grave in Undercliffe Cemetery.

Herbert was the third son of Edith (née Lodge) and James McKell. Born in late 1896 at 15 Beech Grove and educated at Hanson School, he was too young to enlist when war broke out in August 1914. By that time the family was living at 21 Westfield Terrace, a very short distance from Undercliffe Cemetery.

According to the 1911 census, Herbert was working in the laboratory of an analine colour merchants in Bradford and it was this career that ultimately may have cost him his life.

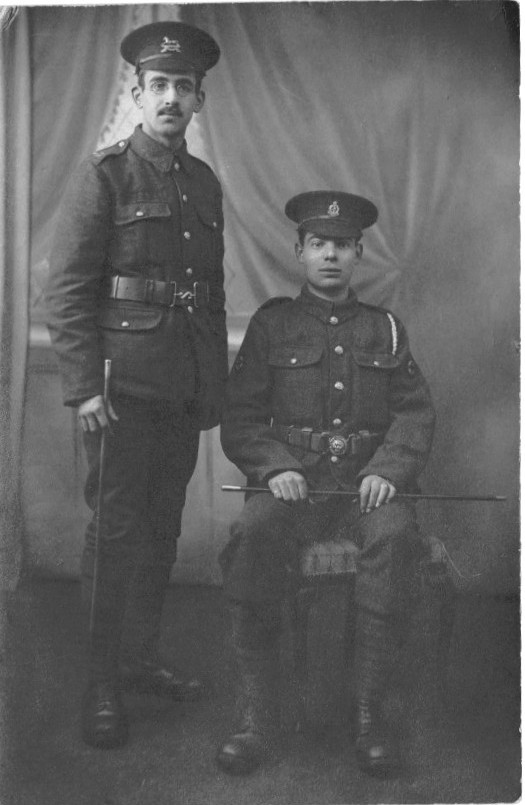

Herbert was in the Territorial Army in Bradford and as such, when he enlisted, he was drafted into the 1/6 West Yorkshire Regiment and started his training for war. Being younger than some of his TA colleagues and therefore enlisting later (on 26 March 1915 according to the Bradford Roll) he did not leave with those who sailed for France on 15 April 1915. His records show that he arrived in France on 24 August 1915, by which time, in response to the Germans’ gas attack at Langemarck in April of that year, Major C.H. Foulkes had been given the task of recruiting and organising ‘Special Companies’ of the Royal Engineers. These Special Companies would form a ‘Gas Corps’ for the purpose of using poison gas against the Germans. Men who had any knowledge at all about chemistry were asked to volunteer for this special role (although knowledge of chemistry doesn’t appear to have really been necessary for discharging cylinders of gas).

There was a sweetener: all men, currently privates (mainly infantry) would be instantly promoted to the rank of corporal – and receive a pay increase from a shilling to up to 3 shillings a day. Herbert’s former career in a dyestuffs laboratory (for which he’d studied chemistry) made him an ideal candidate and he joined the 186th Chemical Company immediately. It must be assumed that he went straight to Helfaut near St Omer in northern France to join new comrades who had commenced training in how to use gas cylinders and the connecting pipes in mid-July. All men were issued with red, white & green armbands – this was so that having launching a gas attack from which they had to quickly withdraw, they would not be accused of desertion.

By early September 1915, it was clear that something was afoot. On 4 September a large convoy of sixty-eight London buses and eight lorries left Helfaut, bound for billets in the village of Busnes near Lillers. They remained in this rural idyll for almost a fortnight until the Special Companies were swept up in the preparation for a major offensive at Loos – the first time the British Army was to use gas. More than 5,000 cylinders, filled with gas from the Castner-Kellner factory in Runcorn, had been brought to various local dumps from where they were carried (in the dark) to front-line emplacements by parties of soldiers, mainly the infantrymen. Each full cylinder weighed 120lbs and was 6ft long – so they were not easy to manoeuvre through the narrow trenches.

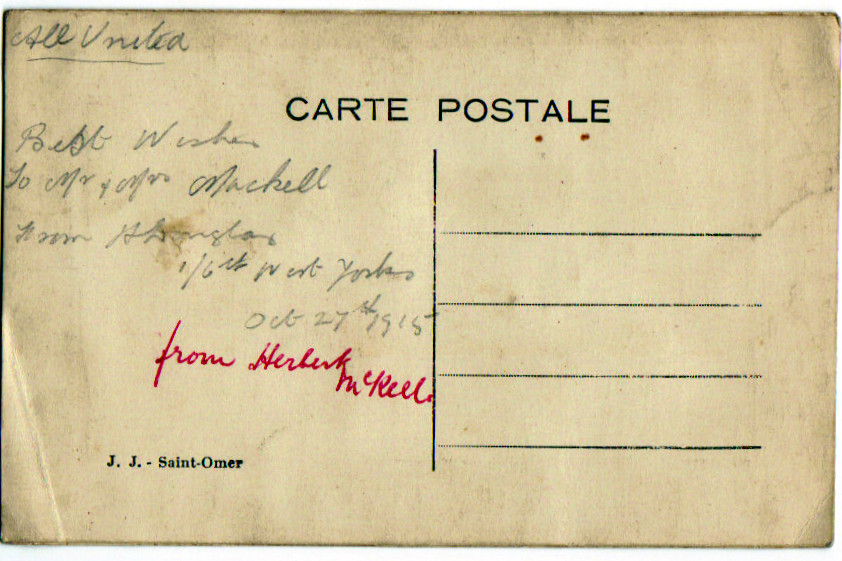

It seems likely that one of these infantrymen was one of Herbert’s TA comrades who was still in the 1/6 West Yorkshires. Within my family archives is an embroidered postcard to Mr & Mrs McKell, sending good wishes. It is dated 27 October 1915 and signed by Harold Douglas.

Herbert’s war records have not survived, however, other records show he was hospitalised, suffering from the effects of gas on 27 September 1915 – making it certain that he fought in the Battle of Loos (25 September–8 October 1915). He was 19 years old and recovered to rejoin his company.

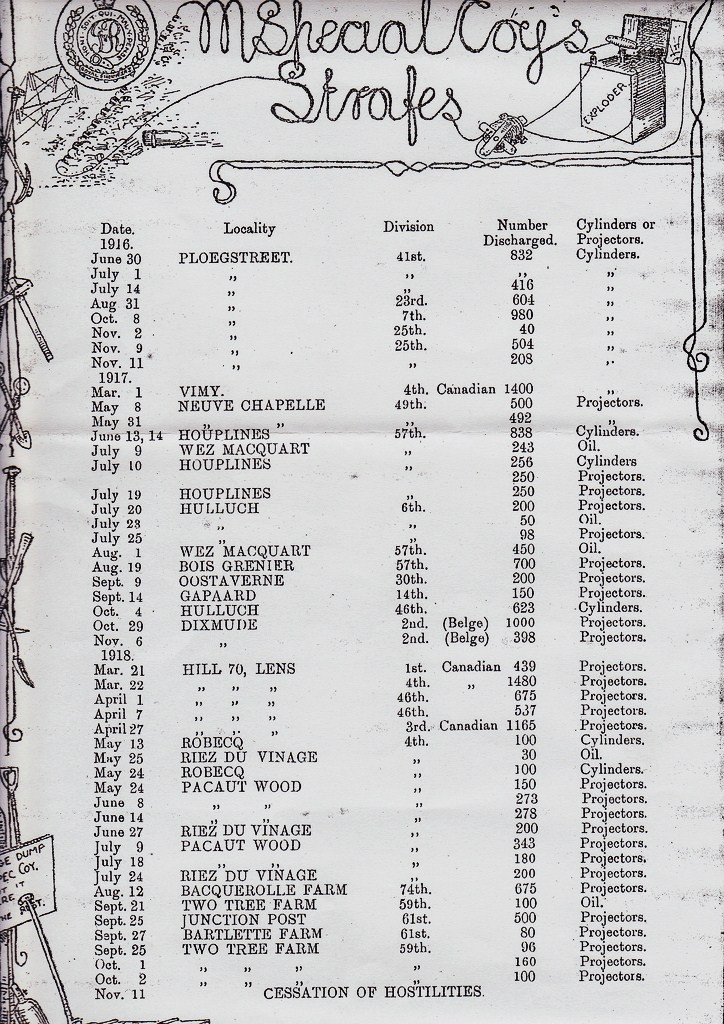

The company was engaged in various gas attacks throughout 1916: two at Neuve Chapelle; two at Hill 70; three at Plug Street – but it was in early 1917, in the preparations for the Canadian assault on Vimy Ridge in northern France that Herbert’s life was cut cruelly short.

In the meantime, Herbert’s elder brother William had finally been accepted into the army, enlisting under the Derby Scheme on 4 December 1915, having been previously rejected three times due to his short-sightedness. The date he was called up is uncertain, however, he was drafted into the 15th West Yorkshire Regiment, underwent training and was despatched to France. By late October 1916 he was at the Somme front and had not been there more than a fortnight when he was injured in his right arm and leg by flying shrapnel. Unaware of the seriousness of his injuries, he walked to the casualty clearing station. William was swiftly shipped out and spent six months in hospital in Dublin, where talented medical staff treated the deep wounds in his leg and saved it from amputation. He was discharged from the army on 22 August 1917, and awarded the Silver War Badge.

Bearing in mind that Edith & James McKell were worrying about their son in hospital in the early part of 1917, sadly worse was to come.

Herbert and his Special Company comrades, now known as M Company, had been deployed to support the 4th Canadian Infantry Division, close to Vimy in Northern France where the Canadian Army was making preparations for the assault on Vimy Ridge.

Preparation began for a raid on enemy lines and by mid-February, incoming troops and horses were being moved into Villers au Bois, a small village to the north-west of Arras and directly west of Vimy, where an army station had been set up.

On 20 February 1917, Lieutenant Colonel Ironside’s (Canadian Division Chief of Staff) secret plan was circulated to twenty brigades (including Herbert’s). Gas cylinders were to be in place by the night of 24/25 February, and troops by 26/27. The weather would be the determining factor in the exact date of the attack; a definite decision being made at midnight.

All gas personnel would wear a red, white and green brassard, with everyone else behind the cylinders at zero minus 10 minutes. There would be two gas discharges: the first at zero hour, 90 minutes before dawn, and a second at 30 minutes after dawn. In between would be machine-gun and artillery fire. Forty minutes after the second gas discharge, the gas personnel would move to the rear and the infantry would advance. The attack finally went ahead on 28 February/1 March and a list of M Company ‘strafes’ shows the operation as one of their largest with 1,400 cylinders discharged.

Initially everything went to plan, but by 4.45am (dawn must have been early) with the wind veering rapidly northward, only a portion of the second wave of gas was discharged. But with the wind changing, the released gas slowly turned and seeped back, saturating the front lines and choking the men. Herbert McKell was one of the nine men killed. A further thirty were wounded.

The Canadian Infantry also suffered heavy casualties; they were committed to the attack and one infantry brigade advanced before the gas cleared. Even two of the commanding officers were killed. It is noted that Lieutenant Colonel Arnold Henry Grant Kemball, Commanding Officer of the 54th, Battalion, Canadian Infantry, knew that Ironside’s plan was badly flawed but had to follow instructions. Leading his men from the front, he became entangled in spools of barbed wire and was shot.

The raid was described as an ‘absolute nightmare’ and the Canadians decided against combining gas released from cylinders and infantry attacks for the remainder of the war.

When the telegram that every mother dreaded arrived at 21 Westfield Terrace, Edith rushed out into the street clutching the telegram, weeping and broken with grief.

A soldier from the Canadian Infantry came to visit the family, bringing with him the buttons from Herbert’s uniform, which Edith had made into a brooch to wear close to her heart. They learnt that Herbert had died as a result of the wind changing direction and blowing the gas back down the trench. How much more they knew I’m not certain – it was probably never talked about much, and my grandmother (who married William McKell in June 1918 at the Airedale College Chapel) decided to burn all letters and mementoes from Herbert saying that ‘enough tears had been shed’.

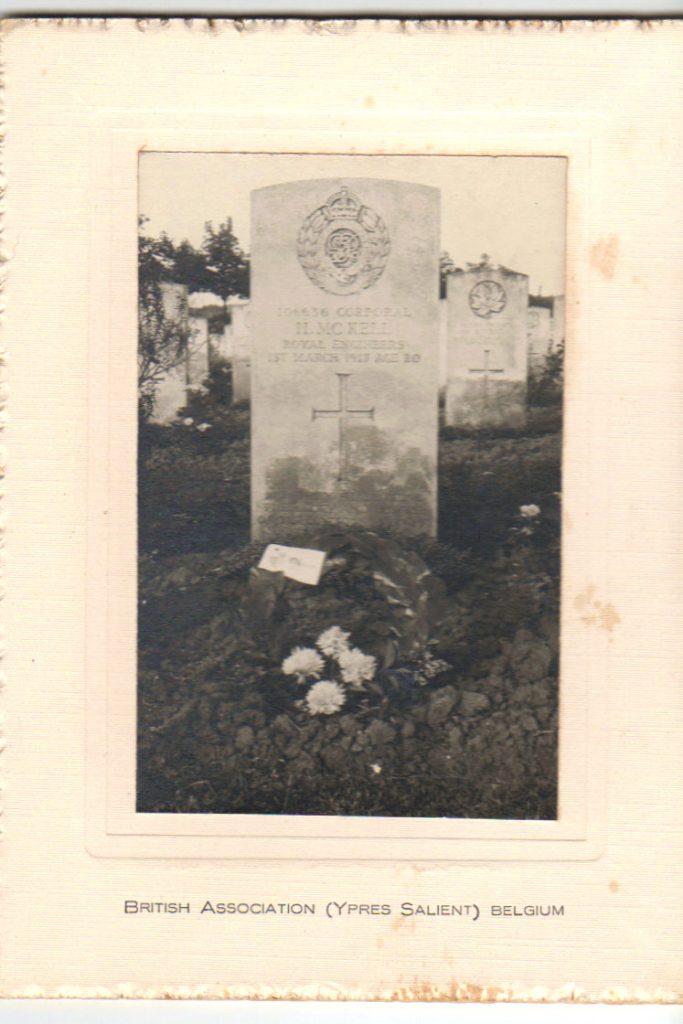

Knowing that Herbert wasn’t killed in some small scale attack; or as a result of gas merely blowing down the trench on an unfavourable wind (as I’d imagined) but in a meticulously planned assault – part of one of the most significant battles (especially for Canada) of the First World War – brings some understanding, but not much comfort. Wilfred Owen’s poem, Dulce et Decorum Est, graphically describes the horror of being gassed, and I hope my great grandparents never learned the full extent of what happened to their beloved boy. Never able to visit Herbert’s grave, his parents sent money to the War Graves Commission in order that a wreath might be placed upon it.

We finally got to pay our respects in 2001.

Gaynor Haliday

September 2020