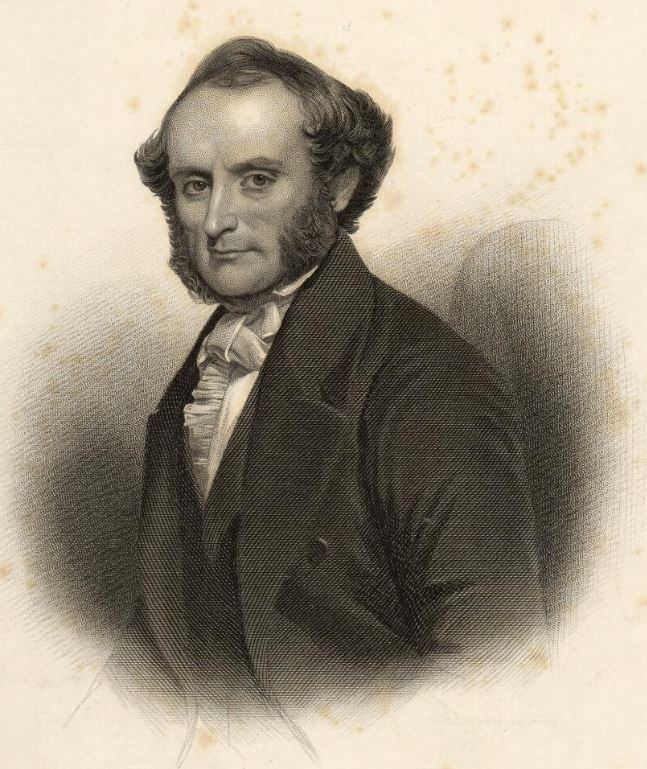

Jonathan Glyde

Jonathan Glyde was born in Exeter, Devon on 1 January 1808, the eldest son of Jonathan Lavington Glyde [“Jonathan L.”] and his first wife Sarah Evans. Jonathan was baptised at Castle Street Independent Chapel, Exeter in July 1808.

After his mother died in 1825, his father married Rachel Arden on 24 April 1828, however their marriage was desperately short as Jonathan L died on 20 June 1828, aged 48.

Jonathan L. may have been a corn factor as he was the only surviving son of his parents Jonathan and Ann (nee Cayme.)

The Glyde family belonged to the Independent church (later to become the Congregational Church,) and as Non-conformists they had a difficult time due to the Acts of Uniformity passed following the restoration of the Monarchy in 1661.The Acts re-established the Church of England and suppressed both Catholics and Protestant non-conforming denominations.

The Act of Uniformity itself is one of four crucial pieces of legislation, known as the Clarendon Code, named after Edward Hyde, Earl of Clarendon, Charles II’s Lord Chancellor. They are:

- The Corporation Act (1661) – This first of the four statutes which made up the Clarendon Code required all municipal officials to take Anglican communion, and formally reject the Solemn League and Covenant of 1643. The effect of this Act was to exclude nonconformists from public office. This legislation was rescinded in 1828.

- The Act of Uniformity 1662 – This second statute made the use of the Book of Common Prayer compulsory in religious service. Upwards of 2000 clergy refused to comply with this Act and were forced to resign their livings.

- The Conventicle Act (1664) – This act forbade conventicles (a meeting for unauthorized worship) of more than 5 people who were not members of the same household. The purpose was to prevent dissenting religious groups from meeting.

- The Five Mile Act (1665) – This final act of the Clarendon Code was aimed at Nonconformist ministers, who were forbidden from coming within five miles of incorporated towns or the place of their former livings. They were also forbidden to teach in schools. This act was not rescinded until 1812.

Combined with the Test Act, the Corporation Acts excluded all nonconformists from holding civil or military office, and prevented them from being awarded degrees at the universities of Oxford or Cambridge.

The effect of these acts was to drive Non-conformists into business and industry where they could still make a living.

Jonathan L. had three sons, Jonathan, William Evans and Lavington. Jonathan became a Minister of the Congregational Church. His brothers entered the textile trade and Lavington, having emigrated to Australia, not only bought and exported wool, he was a money lender and then entered politics.

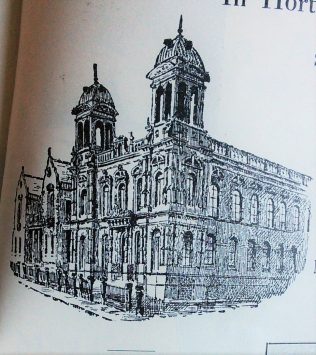

In 1835, Jonathan Glyde replaced the Reverend Thomas Taylor (who is buried in Undercliffe cemetery close to Jonathan) as the minister at Horton Lane Chapel, which was an Independent or Congregational Chapel. The Reverend Taylor had been the minister since 1808 and had been a driving force in promoting the chapel. He was a powerful speaker and did much to promote the religious education of children. He pushed for the building of a Sunday school which was built early in his ministry. The first secretary was Robert Milligan who later became the first mayor of Bradford. Others who took an active interest in the school were: Richard and James Garnett, John Russell, Jonathan Holdsworth, John McCroben, Mr Titus Salt (as he was at the time), Thomas Greenlay, William Milnes, Thomas Wyrill and William McKay. Later, Mr Henry Ripley (later to be Sir Henry Ripley)and Alderman James Law became involved with the school. The interest shown by such individuals ensured that the school was never short of funds.

The Reverend Taylor showed the foresight to be on friendly terms with the other ministers of the town from different denominations. Amongst his co-workers were Dr. Steadman, The Rev. W Morgan, Dr. Benjamin Godwin, Mr John Hustler, Mr Benjamin SeeBohm and Mr John Rand. Together they worked to improve the town by the creation of societies and charitable institutions for the benefit of the Bradford’s inhabitants.

Further, he expanded the church from a small building to a large and commodious property.

Sadly in 1832, he lost his beloved wife and three years later lost his son Thomas Rawson Taylor who was a promising poet. These blows and his advancing years caused him to retire.

Early in his residency, when writing to his wife Jonathan Glyde described his first impressions of Bradford as:-

“Look which way you will see huge tall chimneys pouring forth volleys of smoke, which when you are near, is not very pleasant, but when seen from a distance is interesting enough. There cannot be fewer than a hundred of these chimneys in Bradford and its vicinity; a cloud therefore is continually hanging over it, and this together with the furnaces of the ironworks in the neighbouring hills, the flames from which, though not visible by day, become so by night; have led me to think that Bradford must be a very favoured spot, having, like the Children of Israel, its cloud by day and fire by night”

From his home in Little Horton Lane, he must have been able to look across Bradford to Bowling Iron works to get such a view.

In 1825, Jonathan he married Elizabeth Hull Tyrell. They did not have any children.

Jonathan became a much-loved minister at Horton Lane Chapel. Like Taylor before him, he was driven to improve the lot of the young who he saw walking to work at the mills and foundries each day. Through him the Borough West Schools were established.

He was also one of the driving forces behind the setting up of the Bradford Town Mission.

He had great sympathy for the woolcombers. The woolcombers were a group of employees who were unique to the manufacture of Worsted wool. As such they were often overlooked. They combed wool to produce long, smooth slivers. The woolcombing process was to attach the wool to posts and then using combs heated in what was termed a pot o’four ( a brazier heated with coal or preferably charcoal, that accommodated four combs)brushed the wool fibres straight. As hand woolcombers, this process was carried out in either a small workshop or in the home. There were health implications for anyone in the workshop or home especially when charcoal was used. This was exacerbated by fumes from the different fibres being combed. Alpaca was especially bad. Occupational health implications were not only the problems facing the woolcombers. New machinery that could carry out the combing process had been developed and there were too many combers for the work available. This had the effect of depressing wages. There was also the ever-present fluctuations trade.

It was a general perception that the Northern cities were degrading into overpopulated, unregulated cess pits. The report of 1832 made by Edwin Chadwick highlighted the growing problem, but few improvements were implemented. The Revd. William Scoresby became the Vicar of Bradford in 1839 and was concerned about the living conditions and became instrumental in the setting up of the Sanitary Committee. Due to the schism between the Church of England and the Nonconformist churches, there was a battle for seats on the committee from both sides. One of the members for the Non-conformists was Jonathan Glyde. It was from this committee that the Woolcombers Report(1845) was initiated.

The result of the Woolcombers Report was dire. It showed that over-crowding in the rookeries of Bradford was rife, with poor sanitation, disease and immorality. One entry reported that in Thompson’s buildings on Thornton Road the “air was impregnated by charcoal fumes from hand woolcombers pots of four and were unhealthily close to the mill goit. It found that 95 persons were living in 12 houses and that in one house “a brother and sister worked together; only in one apartment and one bed. She is now left in a state of pregnancy”. The Report recorded that the life expectancy of a woolcomber in West Bradford was 17 years and in East Bradford, 14 years and 3 months.

This report, Like Chadwicks did little to bring relief to the woolcombers and although the Liberal faction, mainly Non-conformists, wished to use the Municipal Corporations Act [1835] to develop a Town Council, which could make sweeping changes to Bradford, it was not achieved until 1847.

Perhaps coming from the fresher air of Dorset made Jonathan particularly aware of the foul air that hung above Bradford and he worked towards the establishing of Bradford’s first park; Peel Park.

In 1826, the land now covered by the park was purchased by Sam Hailstone and this included Bolton House which for the previous two hundred years had been the residence of the Listers. In 1852,The house eventually returned to private ownership but the land remained a public place. In 1863, after Jonathan’s death, the grounds were purchased by the Corporation and turned into a park. It was decided that the park should be named after Sir Robert Peel in commemoration of his works to repeal the much-hated Corn Laws which kept the cost of corn high and therefore, the cost of bread. The opening of the park was carried out by the recently married Princess of Wales, Alexandra who planted two trees named the Alexandra Elm and Albert Edward Oak.

In December 1854, Jonathan died. The Chapel was rebuilt in 1862 but the school remained at Glyde House. The chapel was demolished and replaced by a grander building.

Glyde was commemorated in the street names of Glydegate and Glyde Street.

Jonathan’s younger brother William Evans Glyde followed Jonathan to Bradfordin1837 and in 1841, was living in Manor Row at the home of Benjamin Farar, Painter. William is described as being a worsted spinner. Ten years later he is living not far from his brother, in Melbourne Place off Little Horton Lane. He is married to Lydia, daughter of the aforementioned Reverend Taylor, and has two children. He is described as a manufacturer and worsted spinner, a title he carries forward to the next census. However, by 1861 he is living in Victoria Park, Shipley with a larger family. His move to Shipley is worthy of note as in 1859 he becomes a partner in Titus Salt’s company.

Another ten years finds him retired at 57 years old and living at a residence on Moorhead Lane. His son Lavington Taylor Glyde took over the business. William was still living at Moorhead in 1881. His death on 21 August 1884 was noted in the Saltaire Congregational Church records.

Jonathan, William and the Revd. Taylor are all buried in Undercliffe within a short distance of each other.

Jonathan’s youngest brother was Lavington Glyde (“Glyde”) was born on 24 April 1823. Initially he trained in the accountancy and in the textile trade and the 1841 census saw him lodging at his brother Jonathan’s house in Bradford.

However, in 1850 he sailed to Adelaide, Australia on the Agincourt. He landed in Port Adelaide in July 1850.

He brought a fair sum in cash and a sixty-day draft on the Bank of South Australia, mostly on behalf of relations in Yorkshire. Within a week he lent all his cash at high interest. To his agencies and money-lending he soon added wool-buying and an export-import business on his own account. Later he included wheat and wine to his speculations and even invested in copper-mines.

A Congregationalist, Glyde attended Clayton Church and became active in public affairs. In the 1850s as ‘A Looker-on’ he wrote for the press a series of articles delicately satirical in vein. He supported John Howard Clark in founding the South Australian Institute and served for many years on its governing board. He was successful financial services.

He was an intelligent man and well read. A stalwart Liberal with a strong conservative edge, he represented East Torrens in the House of Assembly in 1857-60, Yatala in 1860-75 and Victoria in 1877-84.

From the outset he was notable for his grasp of constitutional procedures and specially for his competence in financial issues. In 1858 he served on the select committee on taxation and in a ‘protest report’ advocated the total abolition of distillation laws. In evidence to a select committee on the Real Property Act in 1861 he complained that the commissioner’s powers were too great particularly on mortgaged land.

In 1863 he represented South Australia at the inter=colonial conference in Melbourne on uniform tariffs and then became treasurer in Francis Dutton’s eleven-day ministry in July. He was then appointed commissioner of crown lands and immigration under (Sir) Henry Ayers until July 1864. He held the latter portfolio under John Hart for a week in 1865 and under Ayers from May 1867 to September 1868 and again from October to November. He constantly opposed any interference with wool-growers either by the Pastoralists’ Association which, he claimed, ‘wanted to turn the colony into one vast sheep run’, or by government regulations, although in 1867 as commissioner he had to arrange relief for drought-stricken graziers.

Glyde’s greatest work was as treasurer under Arthur Blyth in 1873-75 and John Bray in 1881-84. Always a severe critic of government expenditure he closely watched the raising of South Australian loans in London. He fearlessly fought the National Bank in London and forced it to repay with interest, a five-year accumulation of unwarranted surcharges for floating loans. The total sum was not large but assured British investors of the colony’s budgetary care. In Adelaide he was denounced as pessimist and alarmist and lost his seat in the assembly. For years he fought the muddle and extravagance of departments raising and spending their independent revenues and by 1884 succeeded in consolidating the colony’s funds under parliamentary control even though the change gave the colony the first land and income taxes in Australia.

Glyde’s wife Mary Ellen, née Hardcastle, died on 16 December 1869. On 20 July 1870 at Clayton Church he married her widowed sister Alice Phoebe Kepert. Although marriage with a deceased wife’s sister was legalized next year in South Australia, Governor Sir James Fergusson called it ‘indecent’ and refused to invite the Glydes to a ball at Government House. However, Glyde was gazetted an Honorable in 1875. After resigning from the assembly in March 1884 he visited England with his family. His object was to promote the Talisker mine at Cape Jervis but it suffered heavy losses after he returned to Adelaide. He was accountant to the Insolvency Court in 1885 until he died aged 67 at his home in Kensington, Adelaide, on 31 July 1890. He was survived by his second wife and several children mostly under 21. His estate was valued for probate at £1326.

You can find Glyde’s monument using the what3words App and website. Follow this link and select satellite view. Click Here. If you are using the App on your phone type in speaks.solved.estate in the search box.

Sources:

Pen and Pencil Pictures of Old Bradford – William Scruton

Australian Dictionary of Biography

Research by Deborah Stirling