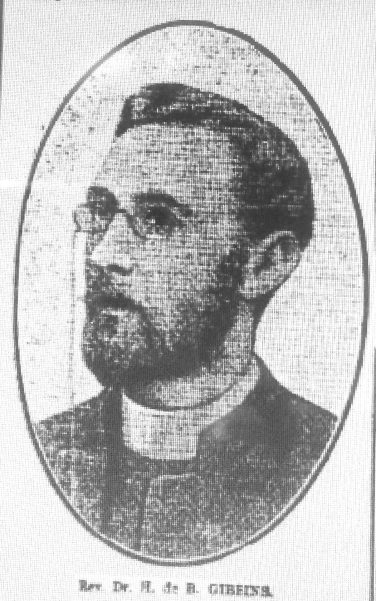

Henry de B Gibbins

Death of a Distinguished Scholar: an unsolved mystery

With headlines similar to this in the local and national press, a tragic fatality in the Thackley rail tunnel in 1907 was destined to be tainted with rumours and speculations about foul deeds. It sounds like the setting for a crime novel by a 19th century predecessor of Agatha Christie: a crime-writer with the gift of sensational storytelling for the newly-literate masses.

This unexplained tragedy took place on 13th August 1907. It was the culmination of a traumatic period for the family of Rev. Henry de Beltgens Gibbins. The gruesome remains of a body were discovered by a foreman plate-layer named James Russell, as he walked through Thackley tunnel. Russell found the body lying between the wall of the tunnel and the rail, about 300 yards from the Shipley entrance. It was evident that a train had run over the body as one leg and part of the head had been practically severed. The body was taken to Shipley mortuary and was easily identified as being the remains of the Rev. Henry de Beltgens Gibbins.

Henry Gibbins was the eldest son of Mr. J.H. Gibbins of Thackley, one of Bradford’s pre-eminent wool merchants. As well as being an ordained priest, Henry was the author of several popular books on economic and industrial history, whilst at the same time he pursued a successful career as the headmaster of a number of well-established grammar schools. Within the previous year, in his early forties, he had taken up the post of Principal of a college in Canada but had returned to England because he found the position unsuitable, and was dissatisfied with the work he was expected to undertake. He had also become unwell whilst in Canada and had decided to return to England despite being an overwhelmingly bad sea traveller.

Since his return from Canada Henry Gibbins had been staying at Colwyn Bay, in the house of his mother-in-law, Mrs Bell. She was the widow of the late Dr. Bell, the Bradford doctor who was renowned for his part in the Bradford Lozenge Poisoning case of 1858, and for his endeavours to eradicate anthrax (also known as Woolsorters’ Disease) from Bradford’s mills. He had been popular, well-known as both a hardworking family doctor as well as a consultant to Bradford’s charitable hospitals, especially the Eye and Ear Hospital. Henry was married to Dr Bell’s third daughter, Emily, and they had a daughter, Eleanor, born in 1899.

Tragically, shortly after Henry Gibbins and his family had left for Canada in 1906, Dr Bell had died unexpectedly, after a long day’s work during which he had shown no indications of ill-health. The respect in which he was held is demonstrated by the obituaries that appeared in local and national papers at the time. Newspaper reports of Dr Bell’s funeral list the great and the good of Bradford, as well as many representatives of the medical profession from far and wide, and of course his son and three other daughters and their families. The absence of his son-in-law, Henry Gibbins, with his daughter and grand-daughter is striking, and it’s a sad thought that they might not even have known of Dr Bell’s death at that stage.

13th August 1907: the tragic day

At the beginning of August, Henry Gibbins came to stay for a few days with his father at Park House, Thackley. On the 13th August he left the house just after 9.a.m. saying he was going for a stroll. But Henry Gibbins was clearly undecided about how to spend the morning. He was to meet his father in Bradford at 2 o’clock, after which he should be catching the train back to Colwyn Bay, using the return half of his rail ticket. But he hadn’t made up his mind as to whether he might delay his return to Wales and his family until the following morning. So, although he wasn’t an enthusiast for walking, his stroll gave him time to mull over his plans for the day. He appears to have decided to call on friends in Apperley Bridge, and perhaps also visit Woodhouse Grove School to indulge his interest in education and school management.

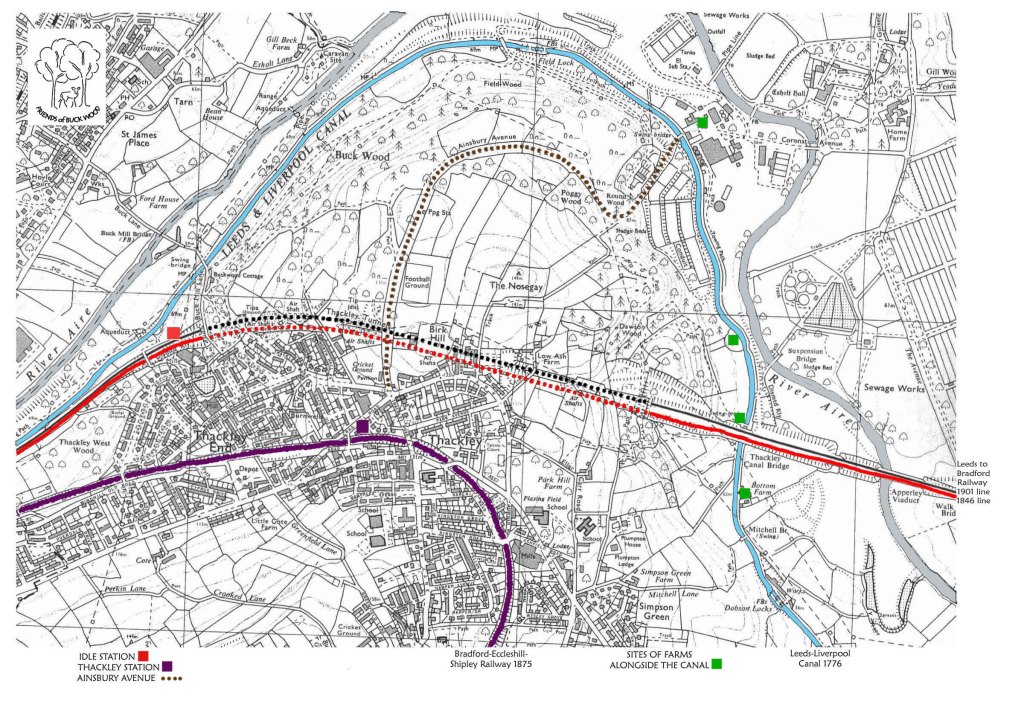

Although Apperley Bridge is only a mile or so from Thackley, Gibbins was not inclined to walk any great distance. He was seen by a porter at Thackley GNR Station catching the 9.25 train from Thackley to Shipley GNR Station at Windhill. At Shipley he crossed to the Midland Station and bought, at some time between 9.40 and 9.55, a first class return ticket for Apperley Bridge. He was assumed to have then caught the 9.59 Shipley connection to Apperley Bridge.

Because of his dislike of walking, Gibbins probably considered two short, connecting train rides preferable to the short stroll of around a mile from Park House in Thackley to Apperley Bridge. And although it was a seemingly indirect route, it was also the one commonly used by local people travelling to Apperley Bridge and beyond.

That was the last sighting of Henry Gibbins alive. At around midday his body was discovered by James Russell, lying between the wall of the tunnel and the rail itself, about 300 yards from the Shipley end of the tunnel. In his pocket was about £3 in money and close to the body was a pair of gold glasses and a letter that he may have been reading. He was wearing a gold watch and chain, which must have been a treasured possession. The watch was still working. and inside was the following inscription, “Presented to J. H. Bell, Esq., by the Woolsorters of Bradford and district, as a token of services rendered in the Woolsorters’ Disease, Bradford 9th April, 1881.”

16th Aug 1907: The Inquest Report

The inquest would have been harrowing for Henry Gibbins’ father, Joseph, especially as it took place within a couple of days of his son’s death. But, as there was no obvious evidence pointing to the cause of death, the state of his son’s mind at the time had to be established as far as possible.

Mr Joseph Gibbins described his son’s academic successes, which included a Classical Honours degree from Oxford, attaining holy orders to become an ordained clergyman, and an award of Doctor of Literature from Dublin University. He had a flourishing career both as an academic writer and as a Headmaster, which had only faltered when his appointment as Principal to a College in Canada had not turned out as expected. And although Henry was obviously distressed by his experience in Canada, his father described him as ‘quite cheerful’. They had spent the previous day together, making plans and practical arrangement for his future, and discussing opportunities that were open to him. Before he left his post in Canada to return to England, Henry had had ‘a vicarage offered’. Perhaps he was anticipating a change of career, into the priesthood? His health had undoubtedly become an issue, and ‘he suffered from a weak heart whilst in Canada’, a problem which was exacerbated by the problems there and the sea-voyages. Prior to the inquest one of the reports in a newspaper (and syndicated widely) stated that ‘the deceased suffered from a weak heart and was liable to attacks of dizziness’. Although this specific claim of dizzy spells was not repeated at the inquest itself, an attack of dizziness could be a relevant factor in these circumstances

The coroner then turned to examining the railway staff and their recollections and actions on that day.

Initially, confusion was caused as ticket staff at Shipley mis-remembered the time when they sold the ticket to Henry Gibbins, but later they corrected themselves, and the times then correlated with the time that Henry Gibbins paid for his ticket from Thackley to Shipley and was also seen to catch the train.

Henry Gibbins’ route and times having been confirmed, questions were then asked of the Shipley staff about the routine checks that should have been made on the train while it was waiting in the station. There was doubt as to whether the carriages were lit, and it was revealed that sometimes even the first class carriages were not lighted, and that on the morning in question they probably were not. The routine safety checks on the doors had taken place according to the station master at Shipley, but it’s unclear as to whether doors were checked individually or just observed as the train began to move off from Shipley.

So there is some doubt both about the lighting and the safety of the doors. None of the doors were open when the train reached Apperley Bridge, but it was acknowledged by the station master there that if a door had been opened, accidentally or deliberately, it would have banged shut again while the train was speeding towards its destination.

Later checks found blood marks on the outside of a third class compartment, further down from the first class carriage near the front which Henry Gibbins had occupied. This is disturbing: it implies that his body was caught and battered against the train and the tunnel sides rather than immediately falling on to the rail below with instantaneous fatal effects.

There is no record of questions being asked about the possibility that there could have been someone else in the compartment that Gibbins occupied. Would the station staff have been able to see if that was the case, especially if the lights were off? There were few possessions found with the body, but might there have been more valuables in, for example, a briefcase, grabbed by an attacker as Gibbins tried to defend himself before the door fell open and he was catapulted into the tunnel? These are speculations, but such attacks did take place on trains, and had happened in the Thackley tunnel. A long dark tunnel and an ill-lit compartment must surely have raised questions at the time? With hindsight, there are several possible scenarios that could be imagined!

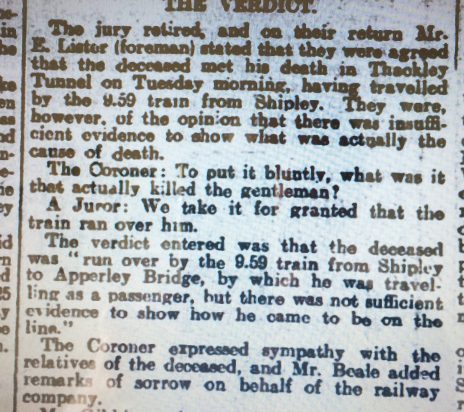

At the inquest held at Shipley on 15th August the jury found that Gibbins had been run over by the train whilst travelling as a passenger but ‘there was not sufficient evidence to show how he came to be on the line’. The evidence suggested that he had been reading a letter (from his daughter) on the train when ‘in some way … he fell out of the carriage’. There was no indication of a crime being committed, or of self-harm being intended. As a member of the Jury summed it up, bluntly, ‘We take it for granted that the train ran over him.‘ It was an Open Verdict.

The funeral took place within a week, at Undercliffe Cemetery. The Shipley Times reported ‘The remains [of the Rev. Dr. H. de B, Gibbins] were removed from the residence of the deceased gentleman’s father , Mr J.H. Gibbins, of Park House, Thackley, to the cemetery, where the burial service was conducted’.

However, that wasn’t quite the end of Henry Gibbins’ role as a ‘Distinguished Scholar’. His book ‘The Industrial History of England’, first published in 1890, and for which he was best known, continued to be revised and reprinted until the 27th edition came out in 1920. It is now available online, (click here) and has recently been reprinted in paper and hardback as a classic work.

But the mystery of Henry de Beltgen Gibbins’ death remains unresolved.

Dr Christine Alvin.

This article is reproduced from Thackley and Idle History Files by kind permission of the author. www.thackleyandidlehistoryfiles.org